This page describes some events in which Dibble men descended from John Dibble of Connecticut and Indiana may have participated.

We can't assume that any particular person participated in a Civil War battle merely because his unit was present at the battle location. As troops move, portions of units are detached and assigned guard or forage duty or placed in reserve, and never get into the fighting even though their unit names show up on battle maps. Individuals may be absent from their units either because they are on leave or sick, or because they are "paroled" prisoners who have not yet been "exchanged". Or they might be "straggling", whether accidentally (they got lost or, being exhausted from marching, took a nap and overslept) or deliberately (they are making themselves scarce in order to stay alive). Without a statement from the person that he was in a battle, or an eyewitness who saw him there, we just can't be sure. With the exception of Alonzo Dibble, we don't have any statements on the record about their war service for any Indiana Dibbles in our line.

Still, it's fun to speculate, and the following stories are presented as "what could have been".

Harvey and John Joseph Dibble

Both Harvey and John J. Dibble, sons of Silas, served in Company D of the 18th. Indiana volunteer infantry regiment. The 18th. Indiana had an eventful career in the Civil War. Among the major battles the unit was involved in were Pea Ridge, and several battles that were part of General Grant's campaign to take Vicksburg.

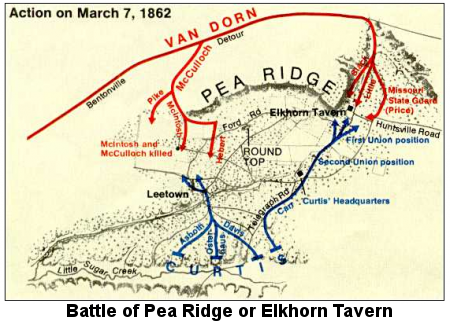

Battle of Pea Ridge, or Elk Horn Tavern

This battle took place on March 7 and 8, 1862 in northwestern Arkansas, where several roads converged around the hamlet of Leetown on the bluffs north of Sugar Creek. Federal forces had pushed the Confederate military out of the state of Missouri, and Union General Samuel Curtis was chasing them into Arkansas. Confederate Major General Earl Van Dorn decided to turn and fight.

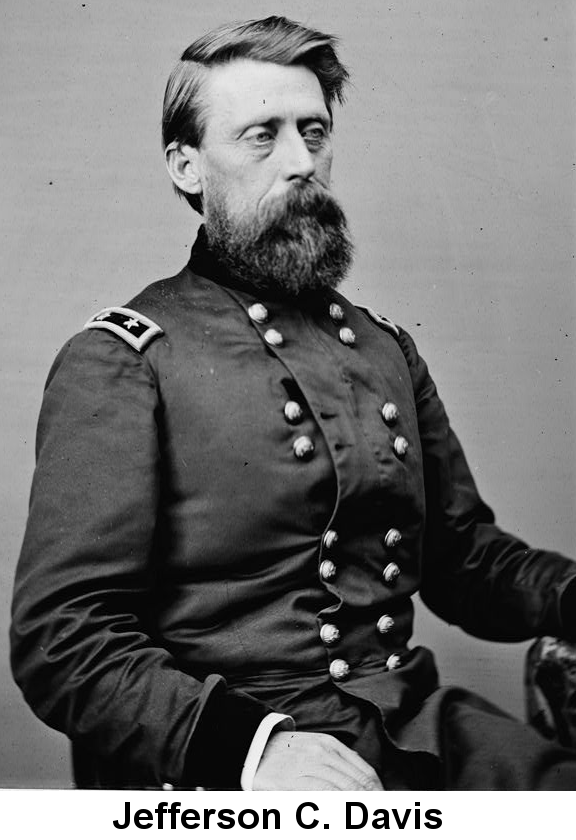

The battle is famous for the errors made by the German Union General Franz Sigel, but this was a clear Union victory. Sigel commanded the First and Second Divisions. The 18th. Indiana, along with two other Indiana infantry regiments and the 1rst. Battery of the Indiana Light Artillery, was assigned to Colonel Pattison's 1rst. Brigade, of the Third Division, which was commanded by a colonel with the unlikely name of Jefferson C. Davis.

On the evening of the 6th., Pattison's brigade held an excellent defensive position facing south on the bluffs, just west of the Telegraph Road that ran north from Sugar Creek, passed east of Leetown and a hill known as Little Round Mountain, or "Round Top", and intersected Ford Road at the Elkhorn Tavern. West of the tavern, on the other side of Little Mountain, the Leetown Road ran south from Ford Road into Leetown.

Van Dorn's plan was to move around the Union right flank and come through Leetown and along Ford Road, then south to hit the Union rear. He began to move during the night of March 6-7, but he got delayed and the Union forces found out what he was doing. They turned around and got north of Leetown before the battle began.

The 18th. Indiana played a major role on the first day. The Confederates sent 4000 men under Louis Hebert south down the wooded flank of Little Mountain east of the Leetown Road, aimed directly at the Union Third and Fourth Divisions. Colonel Davis had been moving up the Telegraph Road toward the Tavern when General Curtis diverted him to block the rebel attack.

Colonel Julius White's brigade was at the head of Davis's column and was nearly overrun by Hebert's onrushing men. Davis ordered a cavalry charge that was easily beaten back. But Hebert's left was unprotected, and when Colonel Pattison's brigade of Hoosiers came up, Davis sent them west along a forest path to turn Hebert's flank. There was some very tough fighting in the woods, but eventually Hebert's men were driven back to the Ford Road.

Davis's division ended up a bit south of the Ford Road and the tavern, where they stayed for the night. The next day Sigel brought his two divisions into the line, making the entire federal force available to confront Van Dorn's army. All of Curtis's forces had been badly bruised, but this was a strong position. On the morning of the 8th., Curtis opened up with a massive artillery barrage, one of the few such barrages of the Civil War that was actually effective in softening up an enemy position. Van Dorn realized the jig was up and he began pulling his men back northeast toward the Huntsville Road. Sigel drove his two divisions at the retreating Confederate right wing, then Davis and his Hoosiers attacked the center.

When Davis's and Sigel's men met at the Elk Horn Tavern there was a lot of enthusiastic hooting and hollering, but meanwhile, Van Dorn and his army managed to slink off to the northeast and escape intact. Even so, this battle settled matters in Missouri for the rest of the war.

The Dibble brothers' Third Division lost 344 men, killed, wounded, or missing, over the two days of the battle, and we can assume that, if they were there, both Harvey and John saw some horrendous things in the woods at the foot of Little Mountain, but they were lucky. Colonel Eugene Carr's Fourth Division lost almost twice as many men, nearly all on the first day.

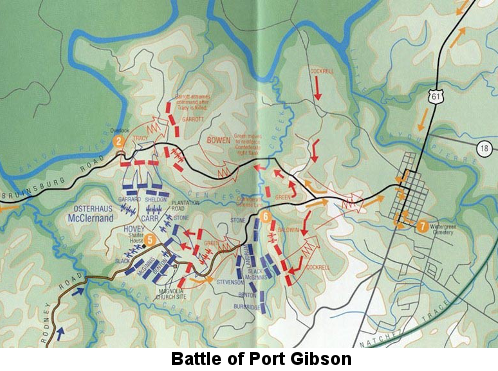

Battle of Port Gibson

By the spring of 1863, the Mississippi River town of Vicksburg was the only obstacle standing in the way of Union control of the entire river from its headwaters in Minnesota down to the Gulf of Mexico. But it was a very tough obstacle, situated on bluffs high above the water and surrounded by swampy, almost impassable land criss-crossed by creeks, bayous, and river channels. The navy could not get gunboats close to the town without being shelled to pieces from the bluffs, and it was extremely difficult to move men and supplies through this terrain.

General Grant's plan was to slowly encircle the region and draw off and destroy chunks of the Confederate defending forces, until he could get close enough to bring the town under siege and force a surrender. John Dibble's 18th. Indiana Infantry was now assigned to the 1st. Brigade of the 14th. Division of General John A. McClernand's XIII Corps. Eugene Carr, the colonel whose men had fought alongside the 18th. at the Elk Horn Tavern, was now the general in command of this division. John's brother Harvey may have been there with him, but we do know that Harvey was temporarily assigned to the 49th. Indiana for some period of time. That unit took part in most of the same battles of the Vicksburg campaign as the 18th. did, so if he wasn't with John, he was probably nearby.

Grant ordered General Sherman to lead a feint attack at the Yazoo Bluffs, about five miles north of Vicksburg, in order to distract a portion of the Confederate forces defending the town, while McClernand's and McPherson's corps traveled south and landed at Bruinsburg, some twenty miles downriver, on the east side of the Mississippi. From there the goal was to move northeast toward Jackson to cut off the railroad supply line to Vicksburg, and, maybe, wipe out Confederate General Joe Johnston's forces into the bargain.

Sherman's feints, made over three days from April 29 to May 1, were very effective, and so McClernand's XIII and McPherson's XVII Corps moved down through the swamps toward Bruinsburg.

Grant did not have a high opinion of General McClernand, and he had originally intended to send him and his men down the river to hook up with General Banks in Louisiana, a state already controlled by the Union, where he could stay out of major trouble. But the federal gunboats that Grant had expected to protect the river crossing had been badly beaten on April 29 by Confederate forces at Grand Gulf, a couple miles upriver from Bruinsburg. This made the crossing operation more dangerous, so he ordered McClernand to stay with McPherson.

It took two days for this group of over 40,000 soldiers to cross the Mississippi, but by May 1 they were ready to move up the eastern side of the river. The first objective was Port Gibson, a crossroads town that would give Grant's forces control of the roads leading north.

The union forces took a two-pronged approach toward the defenders west of the town, with McPherson's corps on the left and McClernand's, with Carr's division, on the right. The 18th. Indiana was serving under Brigadier General William Plummer Benton, arrayed across a road on Carr's extreme right. Carr further broke his forces down into his own double-pronged offensive and pushed forward. His move was initially successful, driving the Confederates through the town and into the river bottoms along Bayeau Pierre to the north. But McClernand, a "political" general, and a largely incompetent one to boot (he had forgotten to issue rations to his men earlier), believed he had routed the enemy and decided to gather his troops together for a review and do some speechifying. Grant warned him that the rebels had just moved off to find a better position. So McClernand arranged his forces into a tight formation with the idea of passing the Confederates on the left, which left his own right vulnerable to a charge that they were barely able to fight off. Both sides then settled down into a stalemate as evening approached. Meanwhile, McPherson's corps rolled in on the Confederate right and threatened to flank them. This forced the rebels to abandon the position, though their rear guard put up a fierce defensive fight to enable the main force to get across the Bayeau Pierre bridge and move north.

The rebels figured Grant would march up the Mississippi riverbank, aiming for Vicksburg, so they occupied an ideal defensive position about ten miles north. But Grant was headed northeast for Jackson, once again outflanking the Confederates and leaving them to tag along behind.

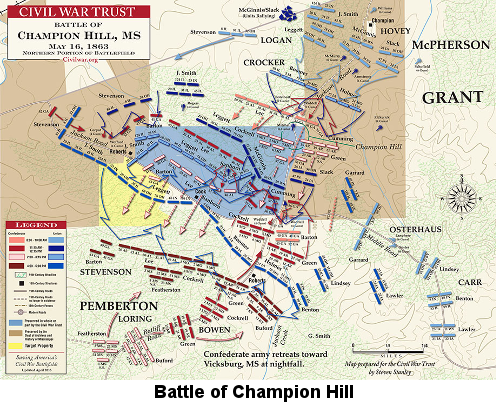

Battle of Champion Hill or Bakers Creek

A bit over two weeks after Port Gibson, McClernand and McPherson had joined up with Sherman at Jackson, taken that city, and were moving due west toward Vicksburg, tearing up the railroad as they went.

Confederate General Joe Johnston had retreated north from Jackson with most of his army, a decision for which he has since been heavily maligned. Pemberton, in charge of the defense of Vicksburg, had most of his troops at Edward's Station, an important point where the railroad intersected with several ordinary roads. About a mile east of the town, Bakers Creek ran roughly north and south, just west of a bald rise called Champion Hill.

Johnston ordered Pemberton to take his 23,000 men east to confront the Union forces. Pemberton knew he was outnumbered and expected a disaster. He was correct.

Grant's Army of the Tennessee had lost some men along the way from Port Gibson, and McClernand's and McPherson's corps had about 32,000 soldiers as they moved west from Jackson. Sherman's smaller XV Corps was ordered to destroy anything of value in Jackson and then move west along the railroad. His objective was to head straight for Vicksburg, but Pemberton didn't know that, and Sherman's route took him just north of Champion Hill.

On May 16, Pemberton got his considerable artillery into a good position on the hill, and his infantry had an even better defensive line a bit further southwest on a ridge that ran along Jackson Creek. Lookouts on the hill saw the Union forces approaching from the northeast and Pemberton began moving some of his men to defend his left flank. This was the wrong move.

McPherson's corps was on the right, and McClernand's corps occupied a line that ran west to east, then curved down to run north to south, on the left of the Union position. The Dibble brothers' 18th. Indiana Volunteers, still under Benton, in Carr's division, were on the extreme left, on the Jackson road nearly a mile southeast of Champion Hill.

McPherson slammed into Pemberton's weakened center and slowly but inexorably drove the Confederates back, first forcing their artillery off Champion Hill, then pushing them off the heights above Jackson Creek. Toward the end of the day, rebel forces under General Bowen mounted a desperate counterattack on the Union left and drove some of them back past the hill, but they couldn't maintain this position. Grant counterattacked with fresh troops and drove the Confederates off the field. They retreated to the outskirts of Vicksburg to make their last stand.

Grant was highly critical of McClernand, whose participation in the attack, he felt, was half-hearted. Champion Hill was a very bloody battle, but McPherson's corps took most of the casualties, over 2500 men killed, wounded, or missing. Still, the 18th. saw some fairly stiff fighting. Late in the afternoon they supported Grant's counterattack, wheeling southwest and piling into the extreme right of Bowen's line. No doubt Harvey and John would have worked hard that day.

The Siege of Vicksburg

The federals pursued the remnants of Pemberton's army west toward Vicksburg, and quickly defeated them at the last natural fortification, the bridge over the Big Black River, on May 17. The rebels retreated into the web of trenches and fortifications surrounding Vicksburg.

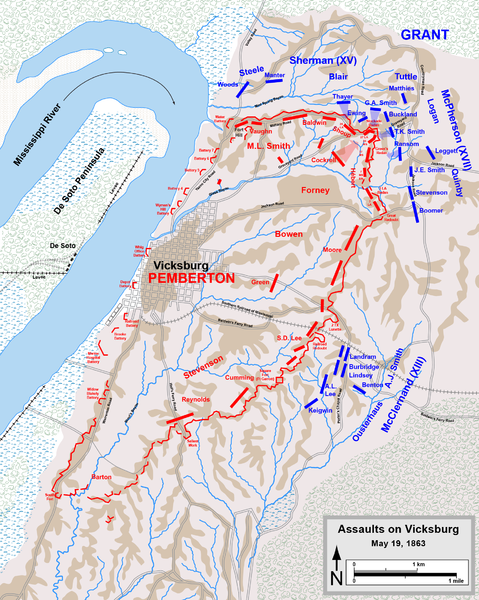

Grant wanted to hit them hard, and immediately, before they could really organize a defense. So he ordered a full assault on the northern flank on May 18, under Sherman. The attack took the Union troops through a deep ravine that was well covered by rifle and artillery fire from a "redan", or fort. They also had to face an abatis, a sort of massive fence made of criss-crossed logs designed to slow attackers down. The assault failed with heavy casualties.

But Grant wasn't yet convinced he couldn't take the city by main force. So he planned another attack, this time using all three of the corps that had been involved in the Vicksburg campaign. He ordered an artillery barrage to soften up the defenses overnight, and sent the troops in with assault ladders. On the morning of May 22nd., Sherman again went in on the right in the north, McPherson attacked the center, and McClernand's men charged ahead on the left.

Harvey and John Dibble, in the 18th. Indiana, would have again gone forward in Carr's division under Brigadier General William P. Benton. Their objectives were the Railroad Redoubt that overlooked the point where the Southern Railroad of Mississippi went through the Confederate lines, and the 2nd. Texas Lunette, a fortification north of the railroad that also covered the Porter's Chapel and Baldwin's Ferry roads.

Sherman's and McPherson's attacks failed. One of the things that the Civil War made clear, over and over, in battle after battle, was that infantry equipped with single-shot rifles, whether muzzle- or -breech-loading, and moving on foot, were no match for well-entrenched defenders using a continuous stream of reloaded guns passed to them from the rear, and supported by artillery firing cannister.

McClernand sent a message to Grant saying that he was facing heavy fighting and needed reinforcements. Grant, perhaps thinking of McClernand's performance at Champion Hill, believed that once again it was McPherson who was getting clobbered and McClernand was holding back, and told him to use his own reserves.

Then McClernand sent a second message that seemed to indicate that he had captured two forts--"The Stars and Stripes are flying over them," he said, and if he got help he could break the Confederate line. Grant showed this message to Sherman, and Sherman agreed to mount another attack. At that point Grant relented and sent over a division from McPherson's corps to help McClernand.

Sherman ordered two more assaults, and when the second one failed with heavy casualties, he told the divsion commander, "This is murder; order those troops back."

McClernand's second message is inexplicable; he had captured nothing. He tried a third time, with the reinforcements sent by Grant, and failed again. Nobody got over the Confederate lines on that day. Total Union casualties for the day were about 3200 killed, wounded and missing, spread evenly over the three corps.

At this point Grant gave up the idea of a quick win. He adopted siege methods, ordering his troops to avoid any loss of life while taking advantage of opportunities to press in closer to the city. For the next six weeks, Vicksburg starved, until Pemberton surrendered on July 4, one day after the Army of the Potomac defeated Robert E. Lee decisively at Gettysburg. Now it was only a matter of time.

On June 6, as the siege bore down, John Dibble was promoted to the officer's rank of 2nd. Lieutenant.

The 18th. Indiana had a relatively easier time after that, participating in a few small battles but mostly doing garrison duty. While taking part in the West Louisiana Campaign in November, John was again promoted, to 1rst. Lieutenant. In January 1864, the entire regiment re-enlisted. After spending a couple of months in Baton Rouge, Louisiana in the spring, where, in March, John received his final promotion to the rank of Captain, the veterans in the unit were given a month's furlough in Indiana.

By then John, and probably Harvey as well, had had enough.

Once back home in Indiana, John resigned his commission and left the army in July 1864.

Harvey's military record says he was "mustered out" on August 8 of that year, but that's not quite accurate. Harvey, with the rest of his unit, had re-enlisted in January and was in for the duration. Unlike John, he was a private, not an officer, so he could not choose to resign. "Mustering out" usually refers to the process of disbanding an entire unit, though it is sometimes used to refer to a single discharge. The 18th. Indiana was not disbanded until late in the summer of 1865. So Harvey was discharged, for reasons we do not know.

Alonzo Dibble

Silas Dibble's son Alonzo enlisted in the US Navy at the age of 15, on June 20, 1864, and he served with the rank of seaman.

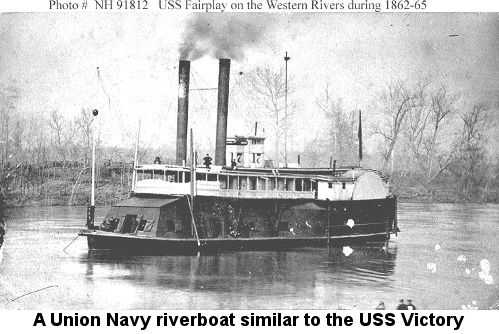

Alonzo served on the U.S.S. Victory (number 33), a naval gunboat that patrolled the waters of the Ohio, Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers. Victory was a wooden steamboat with a rear paddle wheel. It was built in Ohio as a merchant vessel and was bought by the Navy in Cincinnati in 1863. It was refitted as a "tinclad", or lightly armored, gunboat. It carried one 24-pound howizer. The Victory participated in some notable events during the war.

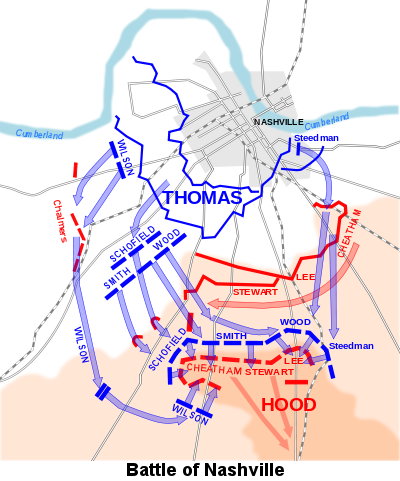

In early November of 1864, the Victory, as part of Lt. Commander Leroy Fitch's Mississippi Squadron, helped defend Johnsonville, Tennessee from Lt. General Nathan Bedford Forrest's cavalry. Johnsonville was a Union supply depot on the Tennessee River, about 60 miles west of Nashville. Forrest had been conducting destructive raids throughout the area for nearly a month, in support of General John Bell Hood's effort to invade the state and take Nashville (in whose defense perimeter Alonzo's uncle John W. Dibble was manning artillery). This battle was largely a standoff between Union and Confederate naval forces. Each fleet did damage to the other, but Fitch did not want to run the risk of taking his boats through a narrow channel where they would be easy targets, so he was not able to prevent Forrest from burning the supply depot, the culmination of Forrest's campaign. Today there is a State Park named for Forrest just across the river from Johnsonville.

A couple months earlier, on September 18, 1864, Alonzo wrote a letter to his mother. Much of it is illegible, and much of the rest is misspelled, but the portions that are readable are fascinating. Military censorship was not routine during the Civil War; letters were usually only censored if they had to cross enemy lines to reach their destinations, or if they came from prison camps, whose commandants didn't want word leaking out about the deplorable conditions in them.

So Alonzo was free to tell his mother where he was and what his fleet was up to. On that day the Victory was near Smithland, Kentucky, at the junction of the Cumberland and Ohio Rivers. They had just arrived there from Evansville, Indiana the day before. The other boats of the fleet, wrote Alonzo, were "laing write by our that is in the moth of Cumberland River," and the men were working on repairing the boats. He hoped the fleet might head back toward Cincinnati and that he might get to visit the family but, he said, "I dont think wont be up that way till or time is out".

He was enjoying himself at that moment: "I went down to Smithland this morning the boys treat me twice to wine and to a watermelong a to a pie... I dont care how much they treat me I can stand as much as they can."

But not all of his experiences were pleasant: "Look Kenneth is gon on a gunbote. I dont think he can git on won becose they have know fleat out there he will be sent on the seven ship and stay ther till we come oup thar thay will be sent to hell and back."

Alonzo described a dispute he was having with someone named Dudley. "I saw dudley he think he is so dam beag he cant speak to our Sharaf wrote a note and sent it over to him. he open it and look at it he look oup and would not say a dam word and sharaf ses he can kiss his ass. and think if I git a chance I will kick his dam head of. [illegible] so he can go to hell."

Alonzo mentioned a letter he had received from his mother Mary the day before, "as you was telling me to be a good boy. I now you know that I am a good boy." Mary had said that his brother John, Captain in the 18th. Indiana, was back home. She said John was sporting "whiskers and mushtas. I suppose you will see me home with the same. Tell John I would like to save him the best kind." Apparently John had travel plans. Alonzo remarked, "I think John will make [illegible] if he gos out to (settle?) in to or three days."

Mary also sent news about Alonzo's brother Harvey, also home from the 18th. Indiana: "Harvey and Zac [illegible] is buchering oh they think they can make it [illegible] at it. I suppose thay can do." And he asked Mary to have his sister Mary Ann write to him.

In closing, he asked his mother to "exguse my bad ritin for I am a bad speler."

Then he added a postscript: "mother you was teling me a bot my sister [gish?] as you fret abot it I am willing to do anything with it if you can [illegible] with it." This might refer to Alonzo's 17-year-old sister Elizabeth.

Alonzo was discharged from the Navy on June 21, 1865 and his boat, the Victory, was decommissioned on the last day of that month. His time aboard had been brief, but it provided him with a lifetime of stories to tell.